PHOTOGRAPHY – A LOOK BACK

I posted these tips on a forum recently. Hope they help:

I started shooting with a Kodak Brownie camera as a kid, won an award from Kodak when I was 12, hitchhiked around SF in the summer of ’68 for two weeks as a teenager with a Canonet, then put away the camera for eight years during pre-med and graduate school.

Eventually I bought a Canon AE-1 in 1976. After learning B&W, I graduated to Kodachrome 25 and a Canon F-1, which was used religiously for the next five years. Then moved to Leica and Leicaflex, Hasselblad, and Pentax 6×7 for another fifteen years. Now I primarily use a three Canon digital SLRs and various lenses from 14mm to 500mm for assignments and a Leica M9 rangefinder for personal work.

In the nearly 30 years I’ve been doing this full-time, I’ve found photography at its highest levels requires a huge commitment from the aspiring amateur or pro. Although you do need to have some talent (an eye), what’s more important is a supreme desire to become better. That means being your own worst critic, practicing your craft relentlessly, and connecting with your subject – for years.

Only once you have established your way of seeing (style), can you set a standard for yourself by identifying your best work and trying not to fall below that mark. Yet, you need to avoid repeating yourself. You need to constantly stretch yourself by trying new treatments, angles, settings, and lighting that all add to the message you are trying to get across to the viewer. Not easy.

The big problem is, if you don’t get the light, foreground/background elements, lens selection, and camera placement right, nothing you do in post-processing is going to elevate the photo beyond a certain point.

The trick is to be in the zone where everything is connected and in homage to what you are trying to say. The best still photographs speak directly to the head and heart. And not always consciously. I’m convinced that truly “being there” is 80% of photography, especially now that the cameras we have are so capable.

Digital has technically made capturing images less complicated, but there is still no “something to say” button. The popularity of phone cameras, Instagram, and similar post-processing techniques have produced a lot of less than successful results. My goal has always been to use equipment and techniques in a way that stretches my personal envelope and does not call attention to itself. I’ll do some “arty” stuff on occasion, but I’m more of a purist at heart.

The human eye does not have the exposure range shown by many manipulated digital images. That’s not to say that there isn’t a place for this treatment in photography, but it needs to look deliberate (i.e. intentional for effect). If your goal is to place the viewer in the scene – where they actually believe they could have been there and seen it that way – then the photo needs to look natural in color and shadowing with a full range of contrast.

If we look at what has happened to still photography in the past fifteen years, we can see that traditional film had a very limited exposure range (maybe four stops for slides). It was very hard to replicate the latitude our vision has. You needed neutral density filters and a skilled color printer dodging and burning to get there. Now with digital, we can not only get there, we can easily go beyond.

We have so much more choice and control in adding/reducing color and expanding the dynamic range today. But with choice comes responsibility. Excessive use of “HDR”, “shadow/highlight”, “fill light”, and “recovery” is fine if you are going for an effect. But that treatment can quickly become unbelievable if the subject’s real characteristics are known to us and desirable.

It’s a brave new world, no doubt. And it’s very subjective. Ansel Adams was a master at translating what he saw as the subject’s possible exposure range onto a print. He was so good at it he had us believing it was real. I suppose that’s the difference between his work and much of what I see today.

I’ve always found that if I have reservations or mixed feelings about a photograph, there is invariably a reason why. I may not be able to put my finger on exactly why it bothers me at the time, but the reason is there somewhere. My recommendation for students who encounter this feeling is to keep re-shooting their concepts. Edward Weston’s “Pepper #30” is number 30 for a reason!

The main thing is to constantly question yourself. Can I make this better? If the answer is no, then you are done and should be satisfied – at least for the time being…

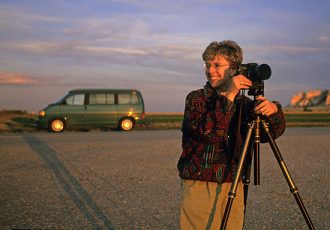

(Photo: By Randy Wells, Andrea Wells somewhere in New Mexico 1996)